We ended Part 2 of this series with CM Evan Glass’s motivations for Zoning Text Amendment 23-10:

Reducing parking near transit is a commonsense approach that will make housing more affordable, help us reach our housing goals, and move us toward a more sustainable, green future.

Let’s examine the motivations individually.

Make housing more affordable

There is no doubt that ZTA 23-10 will contribute to an increased supply of housing, and an increased supply of housing, given constant demand, will lower its purchase or rental price. To what extent is this true?

In MoCo’s Housing Programs and Associated Failure, we quoted county-provided data to report that there is a shortage of 37,000 affordable units. (More accurately, 37,000 families are on the waiting list for housing vouchers with an expected wait time of 6 years.) In Part 2 of this series, I unreliably estimated that ZTA 23-10 can free up construction for 2,500 units. Assuming all those units will be built as affordable, ZTA 23-10 will provide 2,500 ÷ 37,000 = 7% of the shortage. Definitely a reasonable step forward.

However, who is going to build those 2,500 affordable units? If the county government wants to get into that business, it will have to purchase or confiscate the land, procure the materials, and create another bureaucracy to build and maintain the structures. I imagine that some politicians and officials see this as a viable way forward. If, instead, the county contracts with an at-market developer, it will need to provide the land for free, also an enormous expense. (More often than not, at-market developers provide affordable housing only if they receive the land at no cost.)

Alternatively, the county can work through its Moderately Priced Dwelling Units program. This program mandates that 12½% of large residential projects be allocated for affordable housing. If in fact at-market developers build out 2,500 units, then only 312 of them will be affordable, and we are down to alleviating less than 1% of the affordable housing shortage. In that case ZTA 23-10 won’t do much for affordable housing.

A green and sustainable future

In a modern context, “green” and “sustainable” probably equate to a lower carbon footprint or lower environmental impact. Does ZTA 23-10 achieve those objectives? Maybe yes, maybe no.

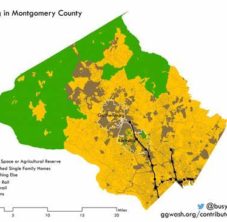

Single-family detached (SFD) homes have a higher environmental impact than skyscraper living. The lawns, the sprawl, the utilities, the asphalt, the long commutes, and the overall resource consumption are higher per SFD unit than per condo. For those people who equate green with lower resource consumption, then, yes, ZTA 23-10 will contribute to a sustainable future.

But that’s only to an extent.

We can say what we want about Manhattan, but one thing is clear: there is an enormous employment base in the downtown and midtown areas. Plenty of residents within New York can leave their homes in the morning, climb into the crowded subways and buses, and with one transfer or less arrive at work. The same is true of Tokyo. That’s not the case in Montgomery County. Our activist residents and their leaders have an extremely hostile and prejudiced attitude toward economic development. If you live in one of the high-density developments right on top of a Metro station, will you also be lucky enough to use the Metro to go to work? If you work in DC, maybe. If you work in Northern Virginia, no. A commuter will take public transportation only if the door-to-door time is less than what it takes using a car. As there are no jobs in Montgomery County, it’s unlikely that high-density housing right on top of a transit center (certainly the Germantown Bus Transit Center) will cut down on commute traffic. The result will be an additional 2,500 units with a minimum of 2,500 extra cars with nowhere to park. That makes our residential housing less sustainable.

Reach “our” housing goals

When free-market cheerleaders talk about housing goals, the discussion distills down to one simple objective: allowing developers to take on the enormous risk of providing housing for what they think the market wants. In a free housing market, the wealthy live in Great Falls mansions and the poor live in modest apartments. Everyone has somewhere to live. When progressive cheerleaders talk about “our” housing goals, the discussion is about control, mandates, licenses, more control, permits, rent control, compliance, vouchers, and ever more control—with the result that struggling families have to wait six years to get an affordable roof. Clearly the free-market position achieves affordable housing, and progressives can’t accept that approach just as they can’t accept the failures their policies engender.

ZTA 23-10 is a surprising and welcome zoning amendment. It removes parking restrictions, albeit to a small degree, that have been blocking high-density development. Should the planning commission and county council continue to break down housing barriers, we will have an increased housing stock for all income levels. In short, we are seeing how a crushingly progressive jurisdiction is taking a small step toward liberalizing its housing market. Everyone will be a winner.