Part 1 of this series summarized a few of the thoughts (out of many) presented by DC affordable-housing developer Patrick McAnaney in his extremely comprehensive series about affordable housing. We learn from McAnaney that zoning has a limited impact on the availability of affordable housing, because other factors are in play that are beyond the control of a municipality. In this installment we explore some aspects of housing policy that need more analysis. Before that, let’s go back to the year 1908 and the introduction of Henry Ford’s Model T (source):

When Ford Motor Company introduced its new Model T automobile on October 1, 1908, the car was the culmination of Henry Ford’s quest to develop an inexpensive, efficient and reliable vehicle that would put automobile ownership within the reach of far more people.

Before 1908 there were automobiles: Karl Benz had his product, as did Gottlieb Daimler. These hand-made vehicles were expensive to make, difficult to operate, and only the wealthy could afford them. Ransom E. Olds was the first to build automobiles (the Oldsmobile) using an assembly line, and Henry Ford successfully put everything together to deliver the miracle of the horseless carriage into the hands of the middle class. Similarly, everyone today, rich and poor, is using software for free; in the 1950s, well within living memory, only the wealthy or the privileged were using software, and that was on clunky tape drives in freezing computer rooms. This is a natural flow of innovation. The first products go to the few wealthy; after that the entrepreneurs, facing a saturated market and seeking ever more profits, figure out a way to reduce costs, expand markets, and deliver the same products at lower price points and at ever higher quality.

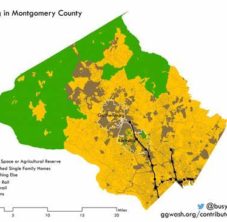

Let’s apply this to Patrick McAnaney’s discussion of “highest and best use” when it comes to land valuations. In Why no one’s building middle-income housing in American cities, he makes the salient argument that when a lot of land is up for sale, the developer building the most upscale project will pay the highest price for the land. This gives us the impression that developers build only high-end projects, never affordable projects. That conclusion is false, because there are only so many residents who can afford the high-end dwellings. After that demographic is housed, fed, and watered, the developers will tend to the next lower rung of buyers, just as happened in the automobile and computer industries. Because they will build only mid-level housing, they will refuse to bid up the price of land. It is precisely because there is so little land available, due to zoning, that developers are incentivized (I would say forced) to prefer building upscale housing. A legitimate question is how much land is necessary to satisfy the high-end consumers, and how much would be remaining for the low-end consumers.

Another factor that requires study is the county’s recent rent control law. The law exempts new construction from rent control, but what will be the effect on the existing inventory? In tightly controlled markets, owners sell their rentals, move into them, or completely abandon them. While MoCo’s rent control law is not as draconian as what we see in Los Angeles, Council Member Luedke acknowledged that “our County now faces real risks of existing rental housing coming off the market.”

Patrick McAnaney’s series proved one thing: relaxing zoning restrictions is necessary, but by no means sufficient, to enable developers to deliver affordable housing. The County Council is gently deliberating its grand plan to allow duplex and fourplex construction on existing single-family lots. I’m all in favor of this reform, of course, but everyone may be surprised that because of the other factors impacting residential construction, we may not be awash in $150,000 condos any time soon.