Today I rejoice, because I was proven wrong by someone with more wisdom and experience than I. Moments like that are as humbling as they are liberating.

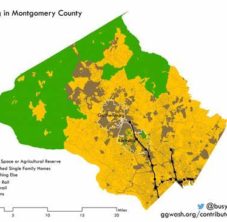

I’ve written quite a few posts about affordable housing, and my claim has been that the way to achieve an inventory of affordable housing is to re-zone. Throw in a few reforms to privatize infrastructure (streets, schools, water), and everyone has a roof over their head. How wrong I was.

Greater Greater Washington ran a long, detailed, and superb series by Patrick McAnaney, a DC developer of affordable housing projects. There is so much to learn from this series. In this post I’d like to emphasize some (out of many) of his on-the-ground insights; in the next post I’ll highlight some aspects that could use better analysis.

In Why affordable housing can’t pay for itself, McAnaney presents a very difficult reality. “Material and labor cost inflation has had an enormous impact on the entire housing market in recent years, as it has in most other sectors of the economy.” There is one entity to blame for inflation, be it duringthe Roman, Chinese, British, German, or American empires: the central government. We can further aggravate that distortion by recognizing that federal student loan guarantees have diverted talented people away from the trades and into white-collar and academic jobs with ever dwindling utility. The difficult conclusion is that even if we eliminate zoning entirely, if the construction costs (material + labor) are inflated beyond what defines an affordable home.

McAnaney also mentions the two top components in financing an at-market or affordable housing project: debt and equity. While affordable housing projects can secure loans at terms more favorable than other housing projects, they cannot escape the impacts of fluctuations in interest rates. Regarding equity financing provided by pension funds and insurance companies, those folks take a riskier position on a housing project than banks; as interest rates rise, they will demand even higher returns as well. Once again, relaxed zoning restrictions don’t compensate for high interest rates.

McAnaney also mentions business cycles and their correlation with construction. In Why multifamily development is so boom and bust, he mentions that the ups and downs of of economic activity tend to be “more pronounced in the real estate market.” Why business cycles occur, along with their magnitude and duration, is a topic of heated research. Most free-market supporters place the source of this volatility on the artificial “management” of the money supply and credit expansion. Regardless, zoning cannot compensate entirely for ineptitude at the Federal Reserve or Department of the Treasury.

Another factor is is the price competition for land. In Why no one’s building middle-income housing in American cities, McAnaney explains that when a lot is up for sale, the project that promises the highest net income will pay the highest price for the land. (Developer A wants to build four upscale condos, and Developer B wants to build eight low-income condos. Developer A’s income stream will be higher, and will be able to offer a higher price for the land.) Relaxing zoning does not negate this logic, and may even aggravate it.

In the next part of this series I’ll address a few points that could use more analysis.