Human relationships are fickle. Probably the most fickle are high-school romances (for those of you who were lucky enough to have had one or two or three). Another example is bloggers on local politics such as myself. We can love our elected leaders, and we can just as easily hand them demerits.

Such is the case with CM Andrew Friedson and his Bill 45-23, Property Tax Credit – Individuals 65 and Above, Retired Military Service Members, and Disabled Military Service Members. This bill expands the property tax credit for senior citizens with the explicit objective of helping them remain in their long-term residences. Before we get into the evaluation, let’s review this legislation’s highlights.

| Eligibility or benefit | Current | Change |

| Age | Certain persons over age 65 | Anyone over age 65, retired or disabled military service and spouses. |

| Maximum home value (assessed) | $700,000 for individuals 65 and older; $599,000 for retired military members and their surviving spouses. | $899,999 with inflation adjustments. |

| Credit available for | 7 years | 10 years |

| Minimum residency in home | 40 years | 25 years |

| Reduction in property tax | 20% | · 20% if earning less than $90,000/year

· 35% if earning less than $75,000/year · 50% if earning less than $50,000/year |

Overall, this is quite a generous expansion of the property tax credit.

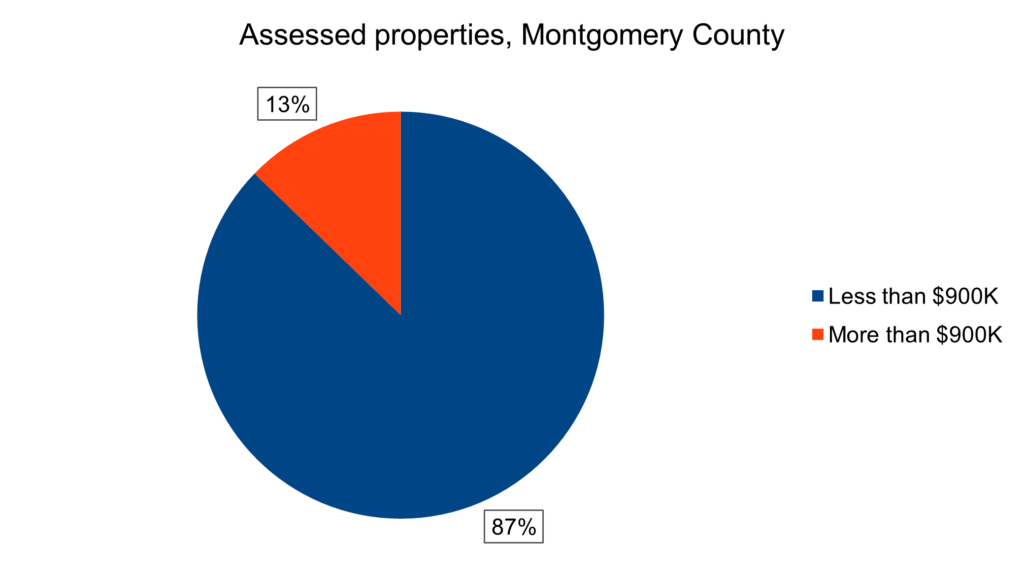

The State of Maryland has a database listing every single property in the state and its assessed value. For Montgomery County, that database shows that there are 351,976 properties. Of those 307,086 (!) of them are assessed at $900,000 or less.

This includes my own home, which is by no means a sprawling mansion in bucolic western Potomac, but is a comfortable structure in a reasonably desirable neighborhood.

The are two really big problems with this legislation. The first is that it uses public funds to help seniors age in place—and simultaneously keeps those residences out of the available housing inventory. If a senior living off social security resides close to a favored elementary school, the county will be subsidizing that senior’s desire to “age in place” and prevent a young family from moving in. Are we sure we want to take an ethical stand that asset-rich, cash-poor seniors have priority to housing over anyone else? Combat veterans are reasonable candidates for this benefit; retired policy analysts arguably less so.

The other really big problem with this legislation is that the distorted financial burden falls onto those precisely blocked out of housing. Sally lives in an $800,000 home in Takoma Park and draws Social Security. Sam, making $150,000/year at his federal IT job, would like to buy Sally’s home. Sally refuses to sell. Sally’s property tax bill drops, and Sam has to make up the difference. Not only does this legislation block out younger families from desirable housing, it demands that those younger families pay for the barriers that keep them out!

I look forward to the day when all seniors can age in place using their own savings. The conditions in our nation’s economy more often than not preclude that outcome. In the meantime, we have to wonder if Bill 45-23 will do more to strangle housing construction than what Friedson’s other two housing bills, ZTA 23-10 and ZTA 24-01, do to encourage it.