This is Part 2 in a series on our county’s distorted housing market. You can read Part 1 here.

When it comes to housing policy in Montgomery County (and probably other jurisdictions), the activists and policymakers ignore science and gravitate to unfounded generalizations that justify a policy they want to implement. Some County Council members and the progressive contingent all talk about “housing security:” housing is a human right, housing costs are too high in Montgomery County, and the only remedy remaining is rent control. In an interview with Montgomery County Media, County Executive Marc Elrich noted, “Creating more affordable housing, long a subject of concern for the county, also registered as a top priority. Current policies, he stated, were not getting the job done.” Let’s see if that’s true.

Availability of moderately priced housing

Housing in Montgomery and PG Counties is quite a bit cheaper compared to other counties in the DC area. A recent search on realtor.com (January 2023) gave the following comparison for the inventory of 3BR/2BA condos with asking prices up to $250,000.

| County | Number 3br/2ba condos for sale less than $250K | Try it yourself |

| Fairfax | 0 | (link) |

| Arlington | 0 | (link) |

| Alexandria | 0 | (link) |

| DC | 2 | (link) |

| Prince George’s | 12 | (link) |

| Montgomery | 11 | (link) |

This brief analysis indicates that MoCo’s housing is already more affordable than DC and the NoVA counties. What is the reason for this phenomenon? Any economist will tell you that the price of housing, just like the price of anything else, is a function of supply and demand. In MoCo’s housing market, the inventory of moderately priced housing is the result of either low demand (the consumers of moderately priced housing don’t want to live here) or high supply (there is already an excess of moderately priced housing). Either way, this example shows that MoCo’s policies of intentionally strangling economic growth have already achieved the goal of moderately priced housing—contrary to County Executive Elrich’s claim that current policies are not getting the job done.

Extent of MoCo’s housing burden

Buckle in, data geeks, this is we prove an important point.

Social activists and mortgage loan officers share one thing in common: how much of a household’s income goes toward shelter. Whether the discussion be about renters or owners, a household dedicating more than 30% of its income to housing is considered suffering from a “housing burden.” In fact, private lenders are extremely cautious about issuing a mortgage for which the borrower will spending more than 30% of income to service the loan, and social activists are concerned with formulating policies to reduce the extent of the housing burden.

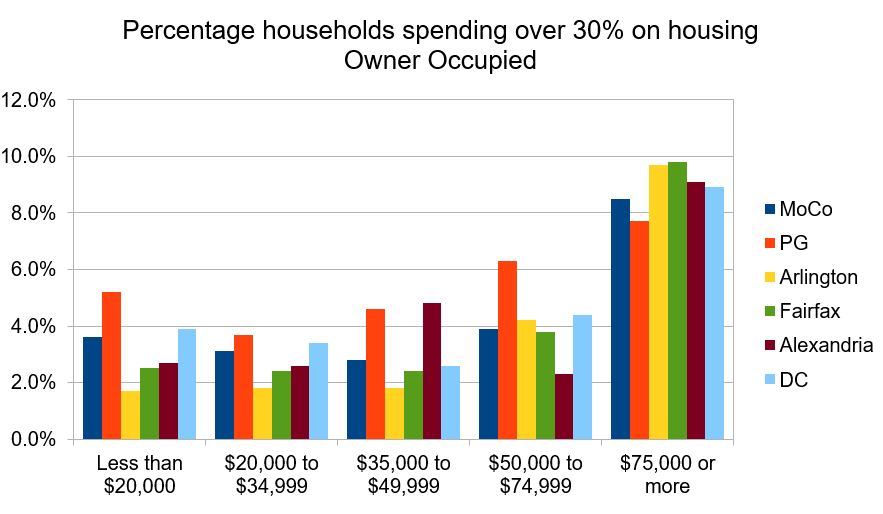

The Census Department publishes Table S2503, which tracks the housing burden nationwide. (Table S2503 for Maryland 2021 is here.) Here is what Table S2503 shows for the housing burden in the DC area among owner-occupied houses.

For example, among MoCo households earning less than $20,000/year in 2021, 3.6% of those households dedicate 30% or more of their income to housing. Similarly, in the $20,000–$34,999/year bracket, 3.1% of households spend over 30% of their income on housing. In either case, a small percentage of those low-income households indeed suffer from a housing burden.

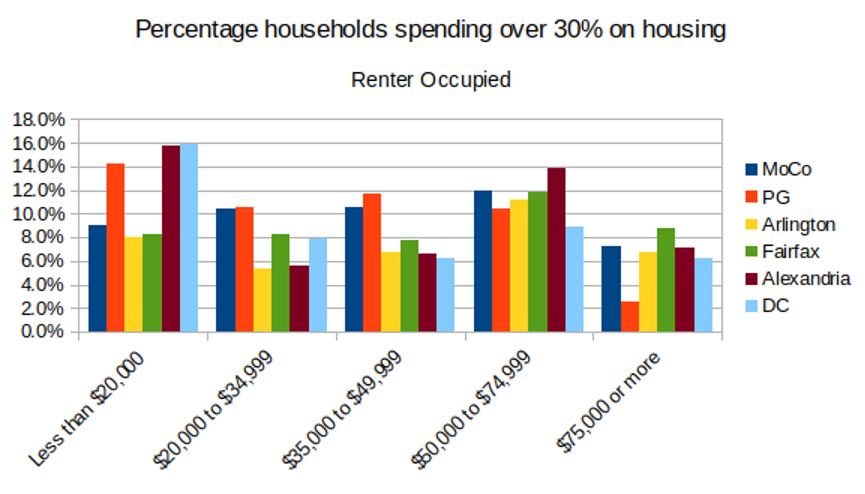

Regarding renter-occupied houses, the situation is worse.

Among MoCo renter households earning less than $20,000/year, 9.0% of those households dedicate 30% or more of their income to housing. Similarly, in the $20,000–$34,999/year bracket, 10.4% of households spend over 30% of their income on housing.

We need to look at these charts and ask ourselves: is MoCo doing any worse than other DC-area counties when it comes to providing moderately priced housing? The comparisons show that MoCo’s policies are in line with the other DMV counties in our comparison. Our county’s policies are just as effective as anywhere else in our area.

The Census Department also tracks income distribution by county. Of Montgomery County’s 388,396 households, 13.9% (53,987) earn less than $35,000/year. Of those households, as we discovered previously approximately 10% (5,400) of them are housing burdened. The implication is that only 1.3% of our county’s low-income households suffer from a housing burden. That is a remarkable accomplishment, and shows that our housing policies are indeed working. There is no need to introduce additional madates, fines, regulations, and other distortions into the housing market to solve a problem that doesn’t exist.

Nevertheless, it’s one thing to peruse census data to prove there isn’t a housing problem; it’s quite different to be a member of those 1.3% of households that are indeed living under a housing burden—and probably other economic burdens as well. Those households deserve attention and a way out. How our county’s policies keep that 1.3% in a perpetual housing burden is the topic of the next post in this series.