Uber drivers are a variegated bunch. Some of them are overworked, some of them have too much free time. Some are chatty, some are sullen. Taking an Uber ride from Denver’s charming Union Station, I scored one of the overworked, chatty ones.

“Where are you coming in from?” he asked.

“Just outside the Washington, DC area.”

“You like it there?”

“Usually, yes, but the mood nowadays is gloomy. I know three people who were recently laid off by Trump.”

“I’ve heard that five of the six highest earning counties are in the DC area. Around Denver you won’t find too much sympathy for DC layoffs.”

Fortunately, I had a short ride and abandoned my driver a few minutes after that conversation.

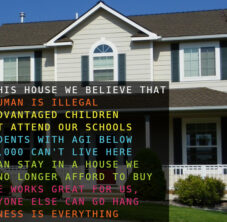

My driver’s perception isn’t entirely accurate. Of the six US counties with the highest median incomes, three of them (Loudon, Fairfax, Howard) are in the DC area. Calvert County ranks 12th, and MoCo ranks 24th (Census data, 2023). No, MoCo isn’t full of highly paid Beltway Bandits to the degree Northern Virginia is.

What is more accurate is that MoCo, along with the entire DC region, is insulated from the effects of periodic economic downturns. Over the past 50 years there have been five significant recessions: COVID (2020), sub-prime (2007), dot-com bust (2000), oil shock (1981), and stagflation (1973). During those difficult times, workers were laid off, businesses closed, households went bankrupt, and neighborhoods turned to slums.

There are two things in common with all those downturns. First, they were engendered by the federal government’s overreach, and for most of those recessions the blame lies with the Federal Reserve Bank. Second, while much of the nation was suffering with social and financial setbacks, the DC area thrived with its ever-growing army of federal workers. The people who are mostly responsible for those recessions didn’t incur the consequences of their actions.

The layoffs happening in our area were also preceded by federal government overreach, in particular the demands by progressives to forcibly engineer the United States (and the world) in their image. The progressives’ DEI and environmental policies put a lot of people out of work, strangled entire industries, denied opportunities to talented workers because of skin color or gender or sexual orientation—and those same progressives were compensated very well for their efforts. Among other things, President Trump and his layoffs represent a reaction to that bigotry. We cannot expect empathy from outside MoCo’s boundary line for our shaky local economic outlook, just as we didn’t have any empathy for the millions of Americans we as federal employees and contractors harshly impacted.

What we can do is look in the mirror and accept the fact that a lot of people no longer want to pay us to do what we think is right. Many of us, particularly the twenty-something feds, will need to adjust to a post-DEI world that we were taught is an obviously necessary reform without recognizing the bigotry they were promoting. Most importantly, we can, and must, reform ourselves so that as government employees and contractors we work for those who pay our salaries in an equal and equitable manner.