Based on downloads available from the state’s board of elections, we can get a good characterization of who financially supported Council Member Kristin Mink during her 2022 campaign, and who received monies from that campaign.

Contributions

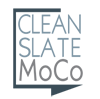

The Mink campaign reported total contributions of $208,683. Who was the number one contributor to that campaign? You were.

All private contributions totaled $74,660, and the balance of $134,022 was provided by the county’s Public Election Fund. (More on the extent of that public funding in Part 2 of this series.)

There were some celebrity contributors. CM Kate Stewart contributed $100, and CM Marylin Balcombe contributed $150. CM Mink herself made a $2,000 loan to the campaign that was repaid (see below).

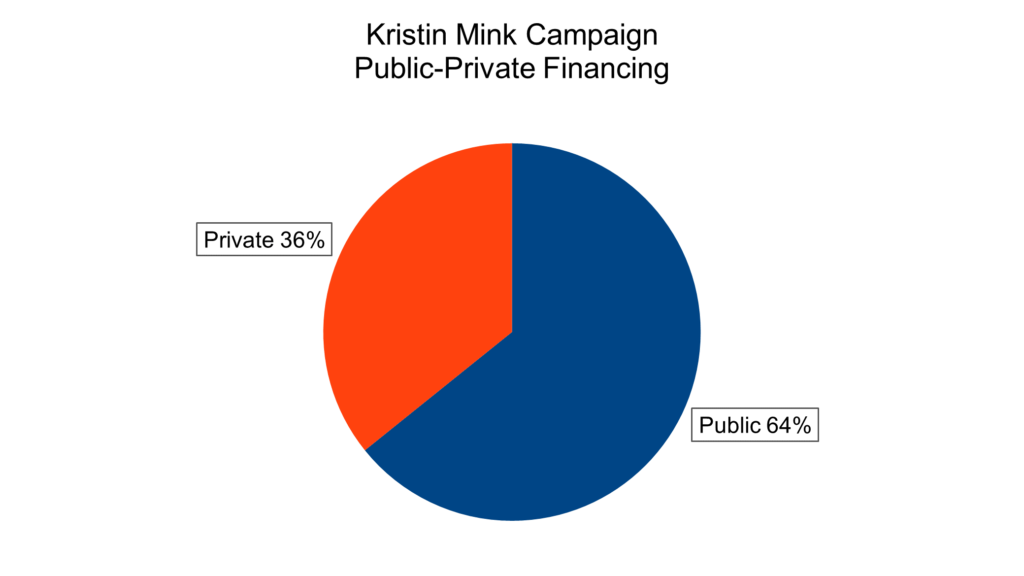

Out-of-state contributions provided 27% of Mink’s war chest ($54,804 vs. $19,856). That’s a slight problem; over one-fourth of her donations, and the influence on her, are coming from somewhere else.

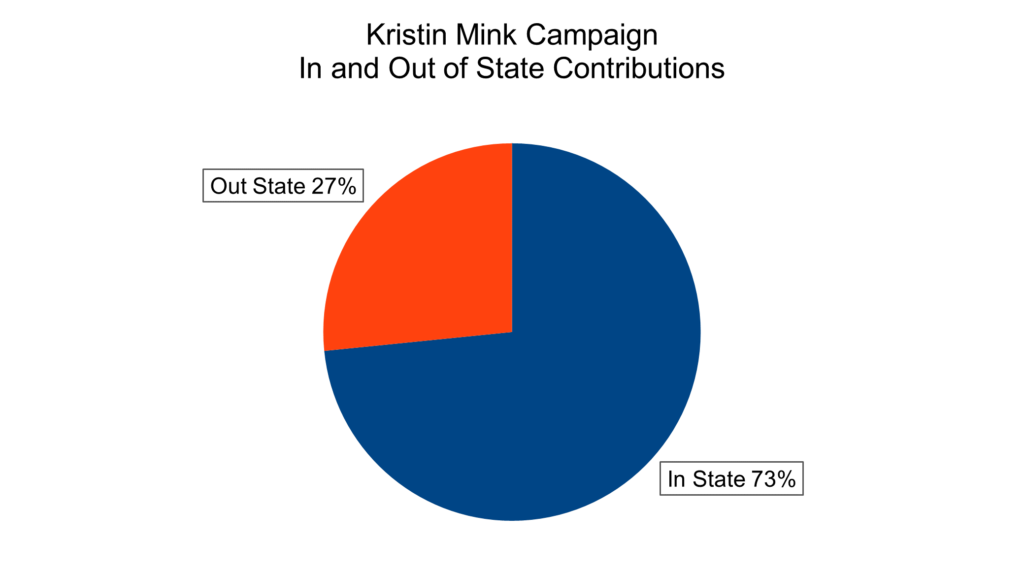

The larger problem is fully 40% of her contributions ($44,542 vs. $30,118) came from outside the county.

Expenses

Two big categories of expenses were direct mailing ($99,000) and online ($36,000). If you want to win a campaign, use Mink’s proven strategy: bulk up on advertising and get someone else to pay for it.

Christopher Willhelm received $15,200 (plus other amounts for reimbursements) as remuneration for consulting. Mr. Willhelm describes himself as an ESOL teacher and union thug at Montgomery County Public Schools. Well, at least one-half of the taxpayer money he took is going for a good cause. Regardless, Mr. Willhelm isn’t a professional political consultant, so why is he being rewarded as such? While all appropriate within the legal framework, how appropriate is it to hire a friend or associate as a “consultant” and give him taxpayer funds? With no reporting requirements applicable to him, we don’t know what he did with those funds.

Lastly, Mink repaid herself the $2,000 loan she made to her own campaign. We’ll talk more about that in part two of this series.

Does public funding of elections work?

We learn from CM Mink’s campaign that even with oversized public funding, and even with influence coming from outside the county—she only won 42% of the vote in the Democratic primary. The purpose of public election funding is to dilute the influence of special interests. In Mink’s case, we see that her sole effort was to score a plurality victory in a very low-turnout election, and any civil rights activist will tell you that a plurality win is something special interests and exclusionists rely on.