The following is an interview conducted by Mark Lautman of Chris Bruch, CEO of The Donohoe Companies, about proven solutions for providing affordable housing. We appreciate the contribution and willingness of both individuals to share with CleanSlateMoCo. Hope you enjoy!

What does Donohoe Companies do?

We build, manage, and develop commercial real estate, including hotels, multi-family properties, and federal facilities. We manage 40 million square feet of facilities and 9,000 apartments in the DC region.

What are some landmark properties Donohoe has built in Montgomery County or DC that people would recognize?

One of our hotels is the Hilton Garden Inn in Bethesda. We developed the Gallery Bethesda. We manage the fountains at the World War II Memorial. We recently completed a hotel, condominium, and residential building in Phase II of The Wharf. We also own what is arguably the most famous gas station in Bethesda, the Sunoco on the corner of Wisconsin and Battery Lane.

What is your function at at Donohoe?

I’m currently the company’s CEO. I’ve been with Donohoe for 35 years. I love my job.

President Biden and his economic team identify land use as one of the primary causes for the lack of affordable housing in urban areas. Do you agree that land use constrains the construction of affordable housing?

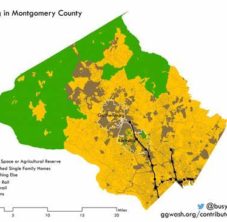

In Montgomery County, there is plenty of land available for affordable housing. It’s just expensive. The county owns undeveloped land, including parking lots, the school system owns land, and the Parks Commission owns land. A lot of public land could be diverted to affordable housing.

The Biden Administration also cites zoning as a blocker for the construction of affordable housing.

Yes, to an extent. Plenty of land is already zoned for single-family detached, and that zoning could be changed to allow duplex properties.

The county imposes a Moderately Priced Dwelling Unit (MPDU) program on new developments. After more than a decade, we see that this program is not delivering enough affordable units. Why not?

Under the MPDU program, developers must allocate 12½% of the units to affordable housing in any project with 20 or more units.

The MPDU program is working, but only to a degree. Residents who make up to 80% of Area Median Income (AMI) are entitled to rent those units, and to a large extent there is enough affordable housing for the upper end of that demographic. The way MPDUs are structured is after a period of time the owner of the building can convert those units to market-rate rental or for sale. As a result, we lose thousands of affordable housing units every year.

What troubles me most is that the demographic that is most severely burdened, those who make 50% AMI or 30% AMI, have very few housing options. The MPDU program is not helping them, and they need housing solutions now. In fact, one report cited a shortage of 26,000 units for the under-50% AMI demographic alone.

Incidentally, there have been proposals to increase the MPDU percentage from 12½% to 20%. The developers would get no subsidies to construct the additional MPDUs. Increasing the MPDU ratio to 20%, without providing additional incentives, will force developers to stop building multi-family projects in the county. The upshot will be there will be no additional MPDUs, and no additional market-rate housing either.

How can the county government deliver enough affordable housing?

If you want private developers to build affordable housing, the most critical component is for the county to make more low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) available.

How do those tax credits work?

The federal government issues a tax credit, typically $8 billion a year, that it allocates in block grants to the states. In a typical scenario, the state allocates that credit to counties, and counties issue them to developers who build affordable projects. Developers can claim those tax credits against their tax liability after the project is put into service, amortized over 10 years.

There are 9% and 4% tax credits based on the cost of development. For example, a developer builds an affordable housing project for $10 million. After putting a project into service, the developer is entitled to a $900,000 tax credit spread over 10 years, or those credits could be sold.

Our county officials should advocate for more credits from the state, and our governor in turn needs to put pressure on Maryland’s members of Congress to get Maryland a larger share of those federal credits.

The limitation with these tax credits is that they apply only to 100%-affordable projects. If a developer puts up 100 units, 90 of them are affordable and 10 are at-market, then the developer is not eligible for the tax credit program. Therefore, market-rate projects with MPDUs, which is 95% of what is being built, is not LIHTC eligible.

Are there other financial incentives the county can offer developers?

Housing Authority Bonds are also an effective incentive. The county’s Housing Opportunities Commission already floats bonds whose proceeds are dedicated exclusively to all-affordable housing. Because the county government guarantees these bonds, they are considered low risk and hence carry a relatively low interest rate. This, in turn, gives developers access to below-market financing for units that are sold or rented below-market themselves.

Tax abatement is another incentive. With a tax abatement, the developer (or whoever owns the affordable unit) pays zero property tax or a discounted pre-construction level property tax for a specified period of time.

Free land is also important for an affordable project. Market rate land prices cannot support an affordable project or anything with more than 12.5% MPDUs, which are not that affordable.

You’ve mentioned three key components for incentivizing market-rate developers to build affordable housing: free land, subsidized financing, and tax abatements. I’m sure there are some readers who are thinking that’s a bit excessive.

If we were talking about building Class A office space with balsamic vinegar shops on the street level, if we were talking about upscale senior living with an on-site valet to park your Audi, if we were talking about a five-star hotel with a concierge who delivers your morning caffè latte to your room—then yes, that would be excessive and unwarranted. Anyone building affordable housing, including a market-rate developer, need access to key affordable inputs—land, financing, taxes—to finance the project. There is no other way for the market-rate developers to develop all-affordable housing. PS, non-profit affordable housing organizations are far more competent at developing affordable housing than market-rate developers.

If incentives for developers is a difficult sell, the county can cut them out by engaging in outright purchases. When a landlord sells a large apartment building, the county has first right of refusal to purchase the building at the agreed price. This works particularly well when the purchase price is well below the replacement cost. It costs between $300,000–$550,000 to develop a new apartment unit today. Wouldn’t it make sense for the county to purchase exiting units, if those units can be acquired below replacement costs, avoiding the time and risks to develop and build, and immediately deliver affordable units to our residents? I’d like to think there are some savvy real estate folks in county government that can spot bargain buying opportunities.

Interestingly, the current credit tightening is also working in favor of affordable housing. Some landlords of large projects cannot refinance their loans because of the high interest rates, and they are forced to sell their properties at prices lower than anticipated, at times below replacement costs. Some of these properties are at transit hubs, which is where I think affordable housing should be. These are ideal opportunities for providing immediate affordable housing.

To finance these purchases, the county can float a housing authority bond, purchase the apartment building, and immediately put all those units up as affordable housing. This takes the developers entirely out of the picture, and also avoids a four-year construction cycle.

Aside from outright county ownership, organizations such as the Montgomery Housing Partnership, Habitat for Humanity, and the Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing have well established records of providing affordable housing without involving market-rate developers. These organizations also have the expertise and skill set required to successfully deliver affordable housing, and access to financing tools, i.e., LIHTC, that market-rate developers don’t have.

Besides the incentives you’ve mentioned, can traditional market forces deliver affordable housing?

There is nothing like excess supply to drive down rents. I’ll give you a perfect example. Go to downtown Bethesda, and you’ll see flocks of cranes putting up high-rise apartment buildings. Granted, those units are on the higher end, but they are not exempt from the laws of supply and demand. The rents in downtown Bethesda are flat to negative, and it will be some time before the excess new capacity is absorbed. It’s the same with any type of housing: the more you build, the more affordable it becomes. Giving developers incentives, offering projects with the Montgomery Housing Partnership, or outright purchases of existing buildings will keep a steady supply of affordable housing coming on line. If we don’t build more housing, the prices will go up, and the demographic earning less than 50% AMI will be affected the most.

When it comes to permitting and licensing, are the obstacles in MoCo worse than any other DC-area jurisdiction?

Commercial development is difficult everywhere. I can’t say MoCo is worse than anywhere else in this regard. Unfortunately, from a general business perspective, the county suffers from an anti-business profile, preventing businesses from locating here. That, in turn, increases vacancies in office buildings and apartment buildings. The danger with this trajectory is that the county is growing overly dependent on residential property taxes.

If you have a large office building that pays $500,000 in property tax, the owner of that building is consuming far less than that in county services. The building doesn’t use the school system, libraries, and parks, so most of the property tax stays within the county’s treasury. In contrast, a young family of four with a $4,500 property tax bill could be consuming $30,000 in services, and that’s only for the public school. Encouraging business growth ensures a net gain in property and income tax revenue. Because that hasn’t been the county’s priority, the County Council is now seriously considering a 10% tax hike on property taxes that could have been avoided.

Closing thoughts?

Market-rate developers cannot provide affordable housing with market-rate inputs. For us to deliver affordable housing, we need affordable inputs in the form of land, public financing, and tax abatements. If the county does its part, the developers will do theirs. If that’s politically impossible, which I understand, then public housing and Habitat for Humanity are the preferred avenues of choice.