This post, part 4 in a series on our county’s distorted housing market. You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

At the time of this writing, the powerful and controlling County Council is considering two rent-control measures that, in the words of the less powerful but equally controlling County Executive Marc Elrich, will provide the solution to the county’s shortage of affordable housing. Apparently both groups believe that the county’s current programs for housing assistance are not comprehensive enough. In this post we’ll examine public assistance in general, and the county’s existing housing programs in particular, and indicate the magnitude of their failure.

Categories of Public Assistance

Since the time of the Romans (and probably before), governments have been attempting to forcibly redistribute a nation’s resources from one favored group to another. Europeans in the 16th–18th centuries used mercantilism to redistribute resources from the poor to the rich (kleptocracies still do so), and since then almost every modern nation has been using socialism and communism to redistribute from the rich to the poor, applying varying degrees of violence to do so.

Efforts to redistribute from the rich to the poor fall into the following categories:

- Cash payments—In these programs, the government makes an outright cash disbursement to the beneficiary. Prominent examples include Social Security and the mortgage interest deduction. Often there are qualifications the recipient must satisfy to receive the payment, such as income.

- Subsidies—In these programs, the government pays suppliers a subsidy to keep the retail price low. Examples include subsidies to farmers for growing certain types of corn and producing ethanol. All consumers benefit from theses subsidies, even those who may not need them.

- In-kind—In these programs, the government reimburses the supplier, in part or in whole, for the resource. Prominent examples include Medicare and SNAP. Only those consumers who qualify for these subsidies benefit from them.

- Direct production—In these programs, the government provides the actual resource. These include public housing (“housing projects”), public hospitals, public schools, parks, and roads.

- Price controls—In these programs, the government alters the otherwise voluntary transaction between two actors. Examples include minimum-wage laws (price floor, from employer to employee) and rent control (price ceiling, from landlord to tenant).

- Confiscation—In these programs, the government forcibly takes resources from one actor, sometimes for payment, and gives them to another. One common example is eminent domain, in which a local government “condemns” private property, takes possession of it, and uses it to provide a good or service.

Traditionally, economists who favor redistribution prefer outright cash payments; politicians prefer in-kind programs as they provide better oversight. Proponents of free markets reject any form of public assistance, and have decades of empirical evidence demonstrating that poverty is best eliminated through the workings of unfettered voluntary exchange.

Nature of housing vouchers

Arguably the largest form of housing redistribution throughout the United States (and MoCo in particular) is in-kind in the form of Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV, previously known as Section 8). This program was inaugurated during the Roosevelt years, and has been renewed and amended ever since. In this arrangement, the federal government undertakes to pay a certain amount of rent directly to a landlord.

Disagreements rage over the effectiveness of HCV. It has been a sincere lifesaver for those families who are in temporary distress; it has also been the cause of decline of otherwise healthy residential areas.

MoCo’s Housing Assistance Programs

Montgomery County’s government provides housing assistance in a variety of ways. Below are four of them.

HCV Disbursements

Montgomery County’s Housing Opportunities Commission administers the federal Housing Choice Voucher program, which is an in-kind assistance. Only those landlords who submit their units to special inspections are eligible to receive the vouchers. Because not all landlords are willing to do this, often there are fewer HCV dwellings compared to the number of eligible tenants. When the supply of dwellings is less than the number of qualified tenants, those tenants are put on a waiting list. The length of the waiting list indicates the severity of an affordable housing shortage.

Public Housing

The Housing Opportunities Commission owns or manages 22 properties, all of which are dedicated entirely to affordable housing. This direct-production assistance amounts to 2,260 dwellings out of 405,000 rental units countywide (less than 1%). There are additional units participating in the Scattered Site Program, in which a portion of a private development is allocated to affordable housing.

Rent Supplement Program

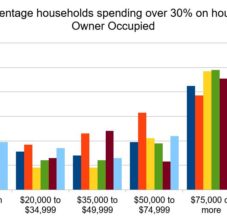

The Housing Choice Voucher program is a federal program managed by the county government; in contrast, the Rental Supplement Program (RSP) is another in-kind program funded by the county’s Department of Housing and Community Affairs (DHCA). This program also provides vouchers to low-income residents, with the goal of ensuring recipients allocate less than 30% of their income to housing.

Moderately Priced Dwelling Units/Inclusionary Zoning

When a builder wants to develop a project, the county government issues a permit subject to the constraint that some of the units be offered as part of the Moderately Priced Dwelling Units (MPDU) program. The goal of this price-control program is for any development of 20 units or more, 12½% to 15% of the units fall under MPDU.

MPDU units can be rented at an amount that does not exceed the tenant’s income, cannot be sold at market rate for a specified period or time, or can be sold only at below-market rates for a specified period of time. The extensive rules and regulations that comprise this program, some of which are finalized during a project’s negotiations, are beyond comprehension.

Failure of these programs

A recent memorandum issued by the county’s planning commission revealed the following:

- There are currently 8,834 active vouchers from various programs.

- There is a backlog of an additional 36,676 applicants for all housing programs (vouchers and otherwise).

- Average wait time for a voucher is 6½ years!

- 19% of voucher holders are still rent-burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on housing.

Furthermore, the number of MPDUs built during 2022 was only 184.

This is how you can identify policy failure: lots of regulations, lots of rules, lots of rhetoric, and 36,676 households waiting an average of 6½ years to get assistance. If you put faces on these households, you’ll find single mothers sleeping in cars with their children, immigrants trying to find a better life, native-born Americans who lost a job or got caught with a hospital bill, or any other household that doesn’t fall into your favored demographic. No matter who is on that waiting list, the personal suffering must be unbearable, and the officials promoting these failed programs are heartless.

(If you want to read about the real cause and solution to affordable housing, read our January 29 post.)

Footnote: Vouchers for housing, vouchers for schools

The preceding discussion revealed that most housing assistance is in the form of vouchers: tenants are given vouchers to live in a dwelling of their choice.

If the county gives vouchers for housing, it should also give vouchers for school choice. Our county’s school board and teachers’ union are viscerally threatened by school vouchers, but if vouchers are good for housing, they’re just as good for schools. More on school choice in future posts.